More Praise for 'Legends of Little Canada' in 'Le Forum' at UMaine

BOOKS/LIVRES, Le Forum, University of Maine, Orono

A reader’s appreciation of Charlie Gargiulo’s Legends of Little Canada by Louise Peloquin

Legends of Little Canada is a passionate love letter with a profound message on “human progress” and “the common good” and how these can be twisted to serve lowly purposes.

It’s a blast-from-the-past time travel into childhood and pre-adolescence, a prequel to Ti-Jean’s Maggie Cassidy.

It is a must-read for anyone who was born in Lowell, has lived in Lowell, has worked in Lowell or is curious about the mill town once dubbed “the Venice of America” which inspired visitor Charles Dickens.

The author shies away from labelling himself as a “professional writer.” But what, precisely, is that? Someone who fills a blank page with words enthusiastic and fresh enough to morph a slim volume into a page-turner has to have some writing skills. The text has all of the ingredients - fun, action, drama, suspense, human interest, violence, tragedy but, most of all, love. You will not find any spoliers here. You readers have to discover the other secret ingredients on yourown.

For years, colorful anecdotes about Little Canada thrilled those who were lucky enough to hear Charlie Gargiulo recount them in person. Transferred to the printed page, they make him a permanent story-teller and thus, a writer.

Those who enter into Legends of Little Canada get to hang out with Charlie’s gang where they will meet buddies and bullies, beloved family members and benevolent strangers, givers and crooks, educators and profiteers.The reader will also hear about reformersfull of dire intentions wrapped up in fake generosity and noble goals. These dealers of destruction end up being exposed as the real boogeymen in the tale. Like charlatans offering relief by pulling, one by one, teeth which could have been saved with a little care and repair, they choose to pull down homes, one by one, and turn a vibrant neighborhood into a painfully cavernous void.

On a lighter note, let’s not forget that younger readers will discover the meaning of loyalty as well as fun street games with neighborhood pals. Older readers will bask in a past that has never really disappeared in the collective consciousness. Whether or not the readers have shared Charlie Gargiulo’s experiences, they will find his prose refreshing, invigorating, rejuvenating, like a walk in a cold cloudburst on a dog day of summer.

A shout-out to Loom Press and its director Paul Marion for publishing this book. Its success will add to Lowell’s clout by casting a light on another facet of the city’s rich ethnic past. Reading Legends of Little Canada is not a honey-coated walk down memory lane. It is a memorial to those who have fashioned us. It is a legacy.

Reading Legends of Little Canada is like re-discovering a favorite Beatles song. Warmth wells up inside when you hear it. You can’t help but smile. You can’t help but cry either.

There are places I’ll remember

All my life, though some have changed

Some forever, not for better

Some have gone and some remain

All these places had their moments

With lovers and friends, I still can recall

Some are dead and some are living

In my life, I’ve loved them all.

—-John Lennon, Paul McCartney

'Legends of Little Canada' Reviewed in England

Beat Scene magazine, published by Kevin Ring in England, with 110 issues to date, has a blog called More Beat Scene First Words in which Kevin reviewed Charlie Gargiulo’s Legends of Little Canada memoir. This blog post is from July 24, 2024.

Late last night I found a package had come through my letterbox. I was just about to go to bed. It was a long day. The day had started at 5 a.m. for me. My wife was away in London with our daughter. So it had been a full on working day for me. It was a book. Legends of Little Canada by someone called Charlie Gargiulo. Now I know Charlie, first met him in Lowell, Massachusetts maybe about 45 years ago. Roughly my age and someone I took an instant liking to. He was a young bloke who showed me around Kerouac’s Lowell. I’d been there a few times before and other Lowellites had shown similar kindness. Back then Charlie was passionate about social equality, a fair deal for working people. And he wasn’t afraid to shake people up in working towards that. And into the mix, he loved Jack Kerouac’s works, even though he told me he was late in discovering him. You probably won’t believe this, but in the 1970s in Lowell Kerouac was a dirty secret. The average resident had never heard of him. Jack Who? I heard this everywhere I went. But there was a pocket of people who tried to keep his name alive in the city. Charlie was right at the heart of that. Charlie had a bunch of friends, to my surprise they were all big into British pop music. The Dave Clark Five of all bands. It puzzled me. Their heyday was long gone. But we had a fun night listening to their LPs and bands like The Kinks. It felt like a time warp, but a good one. I visited a few more times in the 1980s. And now, this book. Well, I put it on the shelf and went to bed. But my dreams woke me I’m trying to find Charlie’s house from back then. In my memory it was near a Greek church with a silver dome, by a canal. Going down all these Lowell streets near Merrimack, the main downtown street. The dream seems on a loop. I get up. Go downstairs and start reading Charlie’s book and I tell you, I’m instantly hooked. Charlie writes from the viewpoint of his 12 year self. He’s a young boy who has been forced, with his mother, to move from Dracut to Little Canada, a more affordable area. There is a reason this has happened and it is an important, crucial reason. But I won’t tell you. I want you to read this book. If you have read Kerouac you’ll know where Little Canada is, or was. It was central to Kerouac’s Lowell books, his life. And here’s Charlie Gargiulo writing about his own life there. It is the early part of the 1960s. I’m 65 pages in. And I’m hooked. Jack Kerouac was alive and sometimes living in Lowell in this decade. But he is a shadow in his hometown. The ex High School football player hero is mostly forgotten in these times. Not sure what’s coming next in Charlie’s book. He’s facing his schoolkid demons. The Catholic church looms large. The priests and the nuns. The book is about Charlie Gargiulo’s Little Canada, a gritty working class area of Lowell. These are his young boy’s memories of it. Beautiful.

Review of "The Power of Non-Violence" by John Wooding, biography Richard Gregg

Book Review: “The Power of Non-Violence” by John Wooding

HISTORY OF POLITICAL ECONOMY, Duke University Press

April 2023, 56 (2), pp. 570-74

A book review by Robert Leonard

The Power of Non-violence: The Enduring Legacy of Richard Gregg. By John Wooding. Lowell, Mass.: Loom Press, 2020. $20.00.

Richard Gregg, philosopher of conflict resolution and peaceful resistance

What kind of historian are you? The kind who prefers to wait in the comfort of the Bodleian while the librarian retrieves your files, or the kind who would rather lug a handcart a mile and a half through the Maine woods in order to retrieve fifty of your subject’s untouched notebooks from a homesteader’s yurt? If the romance of the latter appeals to you, then you will enjoy John Wooding’s account of the neglected American Gandhian, Richard Gregg (1885–1974).

The biographer, an Englishman and self-described ambivalent academic, who spent most of his career in administration at the University of Massachusetts (Lowell), weaves two strands in this book. The main one concerns the life of Gregg, the disconsolate young American lawyer who in 1925 headed off to India to become a disciple of Mahatma Gandhi, thereafter, contributing decisively to the American civil rights movement. The minor thread concerns Wooding himself, a working-class English boy who lost his conscientious-objector father at sixteen and now, many decades later, uses his work on Gregg to explore a paternal relationship sadly cut short. The result is an affecting book, and clearly a labor of love.

The son of a patrician, Harvard-educated church minister, Gregg spent his formative years in Colorado Springs, in the 1880s a gold-rush town and high-altitude refuge for TB patients. His family lived a life of genteel poverty, placed by social status, but not wealth, at the center of the town’s elite. The father favored Harvard men and people of Scottish descent but had little time for anyone else and was no supporter of trade unions. Richard Gregg went to Harvard, like his three brothers, and inherited his father’s religious sensibility but not his political conservatism.

We are told little about Gregg’s time at Harvard, but he eventually graduated from its law school in 1911, emerging into the Progressive Era, with its great social upheaval and demands for reform in working conditions and social life. Initially working for an industrialist brother-in-law, Gregg made a visit to India, where the former was interested in setting up business in jute production. Returning to Boston, he fell under the influence of Richard Grosvenor Valentine, who awakened his interest in politics and social justice, and he became a labor lawyer, specializing in industrial conflict. Several years in this field heightened his distaste for industrial capitalism. By 1924, having forsaken the business world for agricultural classes and farm work in Wisconsin and, decisively, having stumbled upon Gandhi’s writings in Young India, he decided to seek his spiritual fortune in India. He thus wrote a dutiful six-page letter to his family indicating his interest in agriculture, his conviction that American food and cuisine were the cause of physical deterioration, his distaste for the corruption and violence of government and capitalism, and his belief in lived, as opposed to institutional, religion.

That letter—in which Gregg cited the influence upon him of the Webbs, Gandhi, Tolstoy, Veblen, the Bible and the Bhagavad Gita, Thoreau, Bertrand Russell, Franz Oppenheimer, J. A. Hobson, and William James—points to a feature of this biography that will be viewed as a strength or weakness, depending on your perspective. To the reader seeking depth, a list such as this will immediately appear as a lost opportunity for some vigorous probing. What, for example, did Gregg read by Veblen and what did he most appreciate? What did he find valuable in Hobson’s pre-1924 writings? The latter’s debt to Ruskin? His critique of industrialism? What do Gregg’s extensive notebooks, which were central for Wooding’s work, reveal about his assimilation of such influences? This was but one of several points in this book where more detailed exploration of Gregg’s world-making would have been possible. Having said that, deeper probing would have resulted in a heftier biography and, most probably, a reduced readership. Probably wisely, Wooding has aimed his portrait of the life and character of Gregg at the general reader, not the specialist.

Having written to Gandhi, Gregg took the boat from New York on January 1, 1925. His arrival in India coincided with a shift in the Mahatma’s campaign away from direct action and civil disobedience and toward the promotion of social justice and self-reliance, through village education and decentralized household production of khadi or cotton cloth, using the spinning wheel and handloom, in place of imported textile from Britain’s mechanized mills. During his three years in India, Gregg befriended figures such as Charles Freer Andrews, Gandhi’s ally and later biographer; the leader’s son, Maganlal; and, of course, the man himself. He lived at the atter’s ashram at Ahmedabad, entering fully into the life of the community, farming, gardening, spinning and weaving, and writing a simple manual on the last with Maganlal Gandhi. Traveling throughout India, he met Nehru, Tagore, and other figures in the independence movement. For several months, he taught at a school in the foothills of the Himalaya, established by an American Quaker, Samuel Stokes, giving rise to a pedagogical book, A Preparation for Science (1928). Surveying the production of khadi, Gregg wrote The Economics of Khaddar, also in 1928, in which he argued that the social and moral benefits of local hand-production—providing peasants with employment and control over their lives; encouraging personal development—outweighed the efficiency gains of machine production. These arguments would, of course, be subsequently rejected by critics of the Gandhian vision of economic development, armed with the Ricardian analysis of the gains from trade and an arguably narrower conception of well-being.

In two books, Gandhiji’s Satyagraha or Nonviolent Resistance (1930) and The Psychology and Strategy of Gandhi’s Nonviolent Resistance (1930), Gregg laid the foundation for what would later become his The Power of Non-violence (1934). If Gandhi’s argument for peaceful protest was inspired by the Hindu concept of ahimsa, and by Tolstoy and Thoreau, Gregg gave the idea a psychological twist with the notion of “moral jiu-jitsu.” By responding peacefully to violent suppression, Gregg claimed, pacifists threw their aggressors off-balance and gained the psychological upper hand. He also emphasized the element of theater or performance: pacific gestures affected observers and swayed public opinion. Finally, and controversially, Gregg saw military preparation and discipline as essential to the conduct of pacific protest. With the language barrier and loneliness taking their toll, Gregg finally returned to America in late 1928. “Don’t join organizations for reform,” he confided to his diary. “Stay hidden and quiet. . . . Don’t strive. . . . Live with commitment to ideas. Homespun, farm . . . little use of money, simplicity, friendly to all. Simplicity” (quoted on p. 126 of Wooding).

In 1930, now married, Gregg returned to India yet again with his wife, just before Gandhi’s famous Salt March, about which he later wrote in the Nation. In Gandhiism vs. Socialism, published in 1931, he argued for the superiority of the former over both capitalism and socialism, drawing on his experience in India and his wide reading. Here, again, some additional probing of that reading would have been welcome. In the mid-thirties, Gregg continued to eke out a living in the United States, and in 1936, while directing the Pendle Hill Quaker retreat center, published The Value of Voluntary Simplicity. He argued for the deliberate limitation of wants, claiming that an economy based on industrialism and consumerism could never be peaceful, and that the radical simplification of life could provide a corrective to our “feverish over mechanization” (quoted on p. 172). From Wooding’s account, we can infer that Gregg’s belief in the possibility of greater simplicity was predicated upon a more general belief in the possibility of human improvement, which stemmed from his exploration of religion and was presumably reinforced by his observing his own ethical evolution. He would have had little time for the fatalism of homo economicus. His Simplicity was overshadowed, however, by the success of The Power of Non-violence, which soon became a manual for pacifists and peace activists. Gregg was invited to England by the Peace Pledge Union (PPU), where he fell in with Gerald Heard and Aldous Huxley. At the PPU, his strategic ideas were enthusiastically received, but his use of singing, folk dancing, and meditation for the promotion of unity and morale was less popular.

By 1941, Gregg had become very interested in biodynamic agriculture, reading Rudolf Steiner and the latter’s “farmer,” Ehrenfried Pfeiffer. His situation was also changing, with his older wife now increasingly incapacitated by what would prove to be Alzheimer’s disease. For a while in the mid-forties, he taught mathematics at the innovative Putney School in Vermont, but he quit, concluding that he was not a natural teacher. In 1949, he joined Helen and Scott Nearing on their farm in Jamaica, Vermont, eventually building himself a stone cottage there and staying for seven years. Nearing had been a professor of economics at the University of Pennsylvania but was expelled from the academy for his opposition to both child labor and US participation in World War I. In the early 1930s, the curmudgeonly Nearing and his younger musician girlfriend had retreated to a cabin in Vermont, where, thanks to their capacity for enormous labor, they lived a simple, largely self-sufficient, existence. Their Living the Good Life (1954) was initially overlooked but later became a key book for the back-to-the-land movement in the countercultural wave of the 1970s. During his time on the farm, Gregg wrote Which Way Lies Hope? An Examination of Capitalism, Communism, Socialism, and Gandhi’s Program (1951), again emphasizing the violence inherent to both industrial capitalism and state socialism.

In 1952, upset by excessive development in their area in Vermont, the Nearings moved further north to Maine. Two years later, the year in which his long-incapacitated wife died, Gregg published Self-Transcendence, which drew on Christian, Hindu, and especially Buddhist teachings on the matter. By 1956, he had remarried—Evelyn Speiden, a woman long interested in Steiner’s anthroposophy— and the couple were off to India, to spend two years teaching Gandhian economics to students working in the villages. This would soon give rise to Gregg’s A Philosophy of Indian Economic Development (1958), a book that Wooding correctly describes as overlooked but which this reviewer can confirm was influential upon E. F. Schumacher in the work that led to Small Is Beautiful (1973). These two dissenters, quite different in character, provided a bridge between the Gandhian milieu of pre-independence India and the postwar environmental/countercultural movement in the West. Returning to the United States, the Greggs moved to a biodynamic farm established by Ehrenfried Pfeiffer in Chester, New York. It was also around this time that Gregg befriended a Putney School alumnus, Bill Coperthwaite, a young idealist with a Harvard doctorate in education, greatly interested in traditional tools and crafts, and soon to become a renowned builder of yurts, inspired by the Mongolian original. In time, Nearing, Gregg, and Coperthwaite would constitute the central trio in New England’s “alternative” subculture, embracing pacifism, organic farming, manual labor, and the rejection of consumerism. The mid-fifties also saw the development of Gregg’s relationship with Martin Luther King, upon whom the Power of Non-violence was immensely influential, soon propelling him to visit India and ensuring that the energies of Southern civil rights activists were channeled toward largely peaceful methods.

By the early 1960s, Gregg’s health was preventing him from accepting further invitations to India, and the couple were finding farm life difficult. They moved to a small town in Oregon, where, for four years, they grew their own food while Gregg wrote about the Gandhian way and became increasingly pessimistic about the future of humanity. In 1967, they entered a retirement home, where Gregg soon showed signs of Parkinson’s disease. By 1972, he was confined to a wheelchair, and within two years he was dead.

Richard Gregg was a modest, generous man, giving away his things to others who, he believed, would carry the torch. These included Schumacher, to whom he sent books, and Bill Coperthwaite, to whom he entrusted his copious notebooks. In time, it was Scott Nearing’s biographer, John Saltmarsh, at the University of Massachusetts (Boston), who put Wooding on to Gregg and who made the trek through the Maine woods to haul out those notebooks. He and Wooding deposited them in the library of the Thoreau Institute in Concord, Massachusetts, and the author’s subsequent labors resulted in this handsome edition, from the small, and serendipitously named, Loom Press. Gregg’s ideas have lost none of their relevance in the interim decades of accelerating complexity, and his emphasis on voluntary simplicity has been thrown into unanticipated relief by the recent ambitions of the World Economic Forum to impose a version of sustainable “simplicity” from the top down, using the highly complex techniques of surveillance and control permitted by the mobile phone. Those who are dubious about iPhone slavery and complicity with the “Machine,” be they teachers or students, will find inspiration in this portrait of a quiet, dissenting radical. —

Robert Leonard, Université du Québec à Montréal DOI 10.1215/00182702-11055151

Interview with Carla Panciera, author of the LP memoir "Barnflower"

Book club raves about 'Legends of Little Canada'

Author Charlie Gargiulo recently met with these book club members in Lowell to talk about his boyhood days in a riveting, adventurous memoir set in the last days of the French neighborhood in Lowell, c. 1964., just as City authorities began demolishing the homes of thousands of people.

Charlie Gargiulo, center, with Lowell book club members. Thanks to Lisa Corey for posting the photo on Facebook, 12/6/23.

'Jailbird' from Stephen O'Connor's NORTHWEST OF BOSTON: STORIES

A man who had served 20 years in prison for robbing banks in his wild youth told me the story at the center of this story.—S. O’Connor

JAILBIRD

by Stephen O’Connor

December 22nd. Two men sat at a bar in Lowell, Massachusetts. It should have been snowing gently outside the plate glass windows that overlooked Middle and Central Streets, but it was pissing rain. One of the men, Emmet Burke, was gazing out the window, watching the rainfall through the yellow halo of a street lamp and thinking it was another example of how the real never measured up to the ideal, which of course was the White Christmas that Bing Crosby had made famous; Irving Berlin's nostalgic ode to some wonderful days we used to know, a perfect holiday that never really existed—the Christmas in the ads where everyone is wearing warm socks and drinking hot chocolate by the fire and harmony reigns. A beautiful lie. Like people who die in the movies. The sun is setting, and their loved ones are around, and they say some touching and memorable thing or pass on some beautiful secret and expire in the radiance of grace. The truth is, people often die crazy, in some nursing home that smells like dirty diapers, howling at the staff to fuck off and wheezing and gasping for that last breath. But not Bing Crosby.

"You know how Bing Crosby died?" Emmet asked his friend. "You know what his last words were?"

Tony Dos Santos turned away from the TV news, where a professor was explaining that mistletoe was an invitation to sexual harassment. "I made a lot of crappy movies?"

"He should have said that. He said, 'That was a great round of golf,' and he died. Right there on the golf course. He was a hell of a golfer. Better golfer than an actor."

"I hate golf, but that's a good death. Clean."

"Damned right. 'That was a great round.' Boom! I dream about dying sometimes. I'm always in a crash—an airplane or a car crash. And I survive the wreck, but then I know I'm dying. Hope that's not an omen, a foreshadowing."

"I have the same dream over and over—what do they call it?"

"A recurring dream."

"Right. Yeah, I have a recurring dream that I'm back in the slammer. The guard comes by and I ask him, 'When is my release date? Isn't it soon?' And the guard says, 'No, they added a few years, Tony.' And I'm there screaming, 'Why? What did I do?' I wake myself up yelling at the guard."

"That's a shitty dream."

"Awful. Sometimes I jump up with my heart pounding like crazy."

Emmet watched Tony gulp his Michelob Ultra. There were fewer calories, he'd told him, but Christ, that battle was lost. With the extra weight he'd put on after his release and his bad knees, Tony lumbered a bit now, especially after his eight-hour shift in the kitchen of the Falstaff Club. He was a shadow, a fat shadow, of the tough bastard he'd been before he spent two decades in the can for armed robbery.

In jail, he was recruited by gangsters who may have heard of him or seen him box in the Golden Gloves or watched him pound the shit out of the heavy bag in the gym, but somehow, he'd managed to steer clear of any affiliation. Work out and study and do his job in the kitchen; that was his life for twenty years. Got his GED in there, and then his associate degree in culinary arts. A woman who came in to teach a literature class got him into reading; he had plenty of time, and he started to read a lot. He told Emmet he read Jack London, Hemingway, Jack Kerouac, Kurt Vonnegut, Ursula LeGuin—a lot of books—even poetry. If you thought Tony was dumb just because he was a jailbird, you were mistaken. That's why Emmet liked him. He had originally been friends with his younger brother. He'd met Tony through him, though of course, he had heard the stories. Tony Dos Santos was a local legend, or had been. The legend was old now. The young guys didn't even know him. People forget when you're away for twenty years.

He noticed that Tony's beer was empty. He finished his draft and ordered another round. There was a Christmas tree set up at the far end of the bar. When the aging ex-con turned toward him, Emmet saw that the lenses of his glasses were spangled with the reflected blues, greens, and reds of its bulbs. But he also saw, or felt, that the eyes beneath that shower of joyful color were anxious. Jerry, the bartender, brought their beers and asked if they thought the Patriots had a shot at the Super Bowl this year. They both shook their heads and agreed they didn't have the horses. "Father Time is catching up with Brady," Tony said. "And he's undefeated."

"And this fella here knows about time!" Jerry said.

Tony nodded gravely. "Seconds, hours, and years," he said. He spoke the words as if they were a malediction or awoke the memory of pain.

Emmet pushed some bills across the bar and said, "That's good." Jerry nodded and rang the tip bell as he opened the register. Emmet reached for his draft and slid the Michelob toward Tony. To cheer him up, he said, "Dreams aside, you're out, and you'll never be back in the Big House. You're a law-abiding citizen now."

Tony didn't respond. He swigged his beer and looked at the Christmas tree. Finally, he said, "Let's take our beers over to the booth in the corner. I need your advice."

"Sure," Emmet said, and with his cell phone and damp coat in one hand and his beer in the other, he led the way. When they were installed at the table, the older man leaned forward and said, "I want to tell you something. I have to warn you that by telling you, I may be putting you in great danger. So, if you'd rather not hear it, I understand."

"Will I be able to protect myself?"

"Yeah, you just need to keep your mouth shut."

"I can do that."

"This information is dangerous to know because it's deadly to repeat. That's why I'm warning you."

"I get it, Tony. All you need to say is don't tell anyone. I take that very seriously."

Tony nodded and seemed to relax as if he were breathing freely at last. "Good. Good. I do know that. That's why I'm talking to you." He loosened his scarf. "Warm in here," he said and took a slug of his beer.

Someone at the bar yelled, "Who gives a shit about the news? Put the Bruins on!" A cacophony of voices arose. Emmet heard none of it, only the low voice of his companion—the quiet voice of experience, of dues paid, of a life redeemed.

"There's a guy," Tony began. "His name is one you would have heard. A street soldier from a particular gang of criminals. I won't repeat names here because that knowledge can only hurt you. He would kill you if his bosses told him to, or for a fee, or just because he doesn't like you. He'd kill you and think no more of it than you would of slapping a mosquito on your arm. I know him from the old days when I was doing drugs and robbing banks, and he knows me. Now there's another guy. He comes into the club most days, most weekdays, for lunch. And this killer—he wants him dead."

"Why?" Emmet asked.

"Hold off on that for now."

"Okay."

"So, this person, this street soldier, approaches me as I'm leaving the club the other night. I was not happy to see him. Like I said, he's a very bad person. He doesn't live in Lowell anymore, I don't think, so I was nervous. He slaps me on the back like he wants to talk about old times. 'Let's have a beer at the Worthen,' he says. You don't say no, Emmet. So, we cross the street and walk over to the Worthen, get a beer, and sit down, and finally, he says, 'I hear you're a cook at the Falstaff. That's where'—and he mentions this other guy's name—'comes in for lunch quite a bit.'

‘Yeah,’ I say, ‘he's a regular.’"

The door near the two men opened, and they turned to see a couple coming in, lowering a shared umbrella. Emmet had been half expecting to see some scowling street soldier of an unnamed gang. A cheer rose from the bar, and he glanced over at the TV. Krejci had scored and was gliding over the ice, his stick raised in triumph. He squinted to see the score. Two-zip, Bruins. He turned back to Tony, who was thumbing the label off his beer bottle. "So, he asks you about this other guy . . ."

"Right. And he asks me what the guy orders. I say, ‘You know, soup and a sandwich, usually. That's what he likes.’

'Listen, Tony,' he says, 'I need a favor. I'm going to give you something, and I want you to put it in his soup. He won't taste it, and people will think he had a heart attack. Happens all the time. He's in a high-stress occupation anyway. And if they ever found it in him, anyone could have put it in his soup when he went to the men's room or whatever. There's a crowd at lunch, right? You will have cleared off his table and put the rest of the soup down the drain and cleaned the bowl. The poison will come in a small paper container. You burn it at the gas stove flame, or flush it, put it in the garbage disposal. There's no evidence. None. Someone could have poisoned him before he ever got to the club.'"

"Jesus H. Christ," Emmet said. "What did you say?"

"I said, 'Listen, I can't—I can't do that. I'm sorry. I'd like to help you out, but I can't do that.' I told him about my recurring dream, that I'd rather die than go back, that I follow the rules now 'cause I can't do any more time. I'm too fuckin' old. I tell him all that because he can understand it, you see? I don't say, 'I'm not a killer. I never was.' I was a bank robber, Emmet. Yes. But I never shot a teller. I never would have, really. Like that old song says, 'I walked in a lot of places I never shoulda been.' That's true, but a killer I never was."

"How did he take it?"

"He listened, and he stared at me—right into me. I'm telling you when you look into the eyes of a guy like that, you can feel the cold. They have no feelings, Emmet, no sympathy, no conscience. Then he says, 'Five grand now and ten grand after? Would that change your mind? You know, the price is negotiable.' I told him it wasn't a question of money. I just couldn't do it. Finally, he says, 'I understand. People will be disappointed, but I'll explain the situation. You don't have to worry, Tony. I always liked you. When you went down, you kept your mouth shut and did your time. I respect that, and we'll do right by you. Only one thing I'm sure you already know. If it ever gets back to me that you told anyone what we discussed here tonight, I will kill you.' I told him I wouldn't blame him, and he got up and left."

After he had heard the story, Emmet said, "What's the problem? My advice is to shut up. Mafiosos kill each other all the time. You're not going to change that. You're off the hook."

"This guy they want to kill is not a mafioso. He's law enforcement."

"Not my brother! Is that why you're telling me?"

"Not your brother. Your brother would know him. This guy is a prosecutor in the city."

"Shit."

"I told you I wanted your advice, Emmet. That's not true. I guess I want your approval. Like I said, I did a lot of reading in jail, a lot of thinking. Who am I? Who do I want to be? It's almost Christmas, and I thought, how am I going to feel when this guy's family celebrates Christmas without him because some piece of shit doesn't like the way he does his job, and me, I just let it happen."

"You already told the cops."

He nodded. "I ain't gonna die like Bing Crosby, Emmet. But I'm at peace with that. I taped a deposition this morning."

Emmet's brother told him, a month later, that the cops had arrested Greaser DeCola, Mule Murray, and Garret Buckley and charged them with conspiracy to commit murder and a string of other crimes.

"Who were they planning to murder?"

"Tom Benchley, works for the DA. There was an informant. Then they got a wiretap that confirmed the contract these guys were planning to put out. The cops offered the informant witness protection, but he says he's going to stay in the city."

"Well, maybe when they're locked up . . ."

His brother let out a skeptical chuckle. "Yeah. Good luck with that."

Emmet called Tony and pleaded with him to take the offer of protection. There was resignation in Tony's voice. "Come on, Emmet," he said. "I'm old and fat and worn out. Too tired to go count the days in some strange place. That's just another kind of jail. I never wore a mask when I robbed banks. Never liked to hide. Maybe that was stupid. But I won't start hiding now. I did what I did."

A month later, Tony disappeared. His body was discovered shortly after near the Pawtucket Gatehouse, tangled among the debris that gathered at the flashboards above the falls. There were two bullets in his head and the word "RAT" scrawled in marker across his shattered face. Emmet found that he was crying as he read the account in The Lowell Sun. He let the newspaper fall, and his head sank into his hands.

What a crazy world, he thought. We have priests who say they devote their lives to Christ and end up raping children. Respected lawyers whose job it is to help killers go free. Politicians who swear they just want to serve us, and no one can understand how they got so rich. And then you have a convict who dies for a stranger because he doesn't want to think of his kids facing Christmas without Dad.

He looked toward the ceiling and spoke to the spirit of his friend, or to his image in memory: This whole stinking ship is full of rats. But Tony Dos Santos, you were not one of them.

Review: 'The Shape of Wind on Water,' Poems by Ann Fox Chandonnet

From Alaska,, Mike McCormick’s review of “The Shape of Wind on Water,” poems by Ann Fox Chandonnet. Read it here in a flip book version from “Make a Scene” magazine.

Javy Awan, Poet and Publisher, Reviews 'Lockdown Letters & Other Poems'

Lockdown Letters & Other Poems by Paul Marion is a rewarding collection that could have been issued successfully as several books, but together in one volume, the 170-plus pages of poems supply an engaging variety of themes and formats—from pandemic lockdown to tropical vacation spots to space exploration to poetry faceoffs over playoff hockey—and much more.

Most notably, Marion has reinvented the epistolary poem as a collegial email, often cast in the 14-line blank-sonnet form that Robert Lowell favored— an appropriate model and precedent, as many of those poems were letters of address to family and friends. The poems in the Lockdown Letters section also bring to mind Frank O’Hara’s aesthetic of the poem as a personal telephone conversation with a friend—employing direct address in dealing with matters of shared interest and immediate importance. Whether or not these were among the models for Marion’s reinvention of the letter poem, he achieves the same poetic assuredness of those two poets. including the ideals of craft, the levels of inspiration, and the clarity, inventiveness, and directness of expression.

“Salt Creek Beach, Monarch Bay,” a descriptive, narrative poem, conveys the effect of watching a master Impressionist painter at work on a vast canvas, capturing the changes of light, and of time itself, in the scene until the “final fraction of sundown.”

Also admirable is the way Marion writes about sports—how sporting events can structure memories and deepen friendships. Not long after reading the prose poem “Sweeney’s Pond,” I enthusiastically shared its insights with two poet friends—the way that a sports activity can bridge time with old acquaintances, bring back memories, give perspective to the present, and frame future plans. Sports also create community, a topic Marion also explores in poems about his French Canadian heritage and his youth in Lowell.

Like William Carlos Williams, Marion finds poetry in his immediate surroundings—clearly he’s surrounded by gold, by treasures, and he shares these verbally, eloquently, and liberally.

Marion comes across throughout the poems as a man of letters, a literary statesman who wears his credentials easily and casually—he is ever amicable and approachable. Lockdown Letters & Other Poems immensely enjoyable—inventive, insightful, and inspiring.

— Javy Awan

Javy Awan has edited national professional association magazines, books, and journals. His poems have appeared in a variety of publications. He lives in Salem, Massachusetts, and is cofounder and publisher of Derby Wharf Light Box, a local poetry chapbook series.

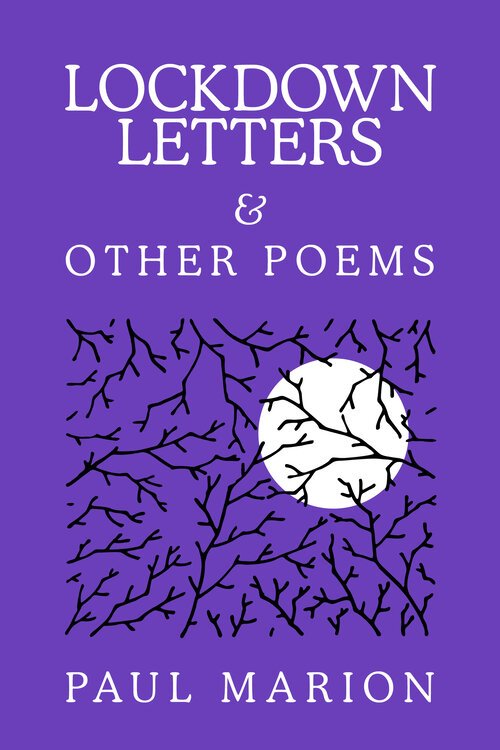

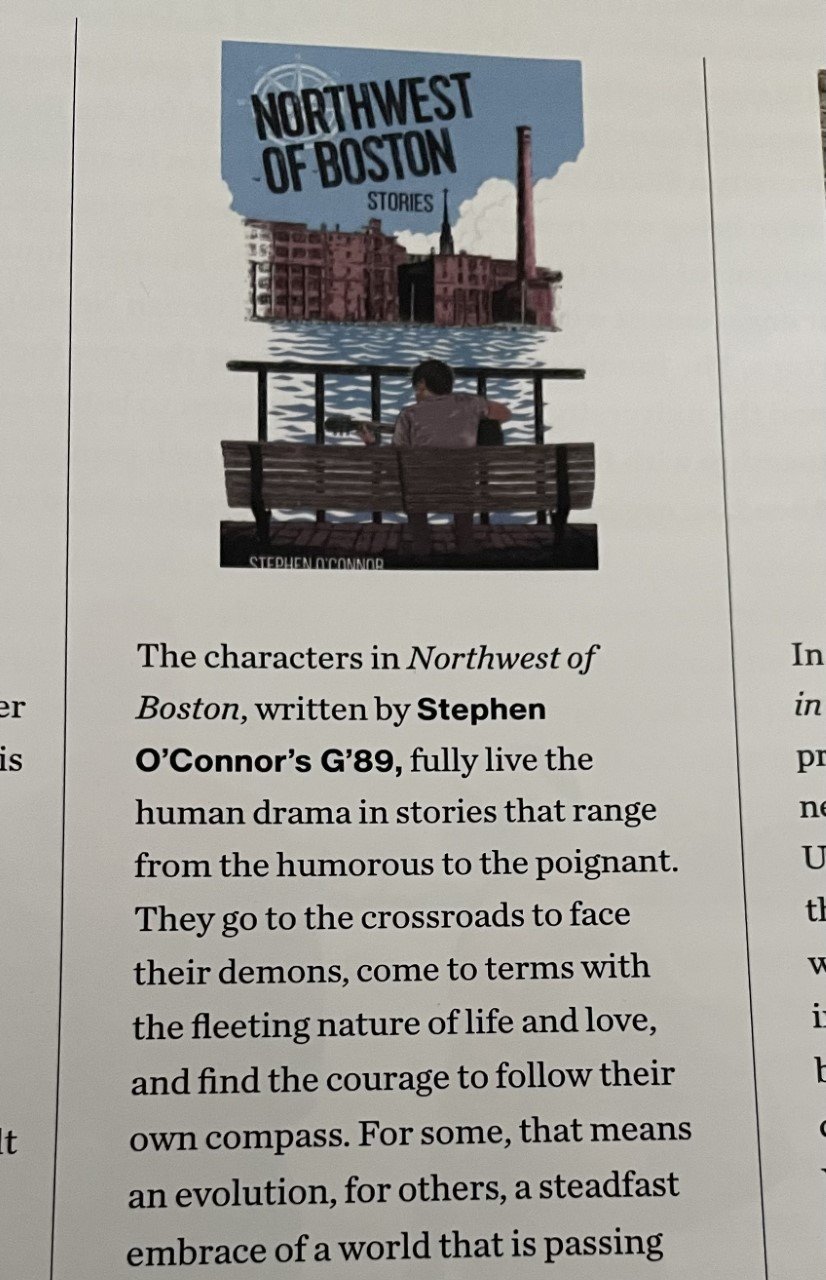

A story from Stephen O'Connor's NORTHWEST OF BOSTON collection

This is a short story from Stephen O’Connor’s Northwest of Boston collection (Loom Press, 2023). We will be featuring excerpts from this book and others this fall. If you enjoy the story, please consider ordering the book from our website. — Paul Marion, Publisher, Loom Press

July 19th, 1969

By Stephen O’Connor

Saturday night. Jack Sheils stopped at the corner of Westford and Coral and leaned against a telephone pole. “Outa shape,” he muttered. He should never have taken the desk job at the post office. Up until five years ago, and for the previous nineteen years he’d been on his dogs, walking the South Lowell route every day. And before that, he was drilling with the 5th Infantry in Northern Ireland and then marching around Normandy and into the Rhineland. The Red Diamond Division under General Stafford Leroy Irwin. Their motto: We will.

He clasped his short-sleeved shirt between a thumb and index finger and gave it several tugs to feel something like a breeze on his chest. Gazing upward, he saw that a few stars were visible through clouds, yellowed somewhat by the city lights. He recalled as he walked on into Cupples Square that it had been named after Lorne Cupples, a WWI soldier who suffered severe stomach wounds near Verdun. After visiting him, the chaplain wrote to his family, “He will die like a soldier, and that is the greatest thing to do.”

Jack set off through the square along Westford Street, some part of his mind, as ever, wandering the old paths of war and remembering some of those faces that would not be seen again. But his mind also kept turning to the Americans out there in space, beyond help, hopefully not beyond prayers, relying on machines to get them to the goddamn moon and back. Machines break down, which was why he was on foot. He had bought a 1964 Ford from a guy in Pawtucketville. “Runs like new,” the guy said. It had, for a while. But engines malfunction. Parts give out. Joey Geoffroy was putting in a new water pump for him on Monday, so Jack had to hoof it for the weekend. The car was a Galaxie Sunliner. Joey pulled a water pump out of a wrecked Galaxie Victoria, but he said it’d be compatible, and Joey knew.

He wondered if the Apollo craft had a water pump. Ah, but a dried-out seal, a loose belt, an oil leak; any of the thousand glitches in a complicated machine could spell doom for those spacemen. They must have great faith in the engineers and in the men and women who put the rocket and the capsule together. Great courage, too. Courage to spare. There were always those who would say, “We will.” Even after the last crew was burned alive on the launch pad. He told himself that NASA had learned from that tragedy, and, after all, it was no Ford Galaxie they were taking out to the galaxy.

A couple of drunks were hollering incoherent accusations at each other outside the Highland Tap. A gaggle of co-drunkards had issued from the bar and were trying to separate them and calm them down. How quiet it must be on the moon. Jack had even heard birds in the Ardennes, and you wouldn’t believe they would stay in those cratered forests where trees fell like so many matchsticks under a rain of German artillery. But on the moon, there were no birds, no crickets, no Harleys thundering past, no howling drunks. The silence must be terrifying. Only the sound of your own breath—inhale and exhale—inside that claustrophobic helmet. Terrifying. To be stranded alive on the moon if the engine failed—a lonely death in silence—sympathetic radio voices. But then, they knew that well, and as Shakespeare said, the readiness is all. Sometimes, during the siege of Metz, at the Bulge, or later, smashing through the Siegfried Line, Jack had envied the dead. The torn limbs and the thousand-mile stares, the screaming missiles, the frantic digging at the frozen earth—it was all over for them.

He supposed that the idea of safety was an illusion down here. After all, as they say, the earth is just a big spaceship. But the illusion is comforting. Our tether to life seems more secure on solid familiar ground, though many are happy and healthy tonight who’ll be dead before the astronauts are scheduled to return. Mary Jo Kopechne was a carefree young girl when the astronauts set off on their mission, and she had already drowned in a car.

And look at poor Finny Doyle. Jack hadn’t seen him in years; then today when he was driving with Joey G. down Parker Street to go to the scrap car lots on Tanner Street, he saw him getting out of a car with a woman Jack didn’t know. “Slow down a minute, Joey. I know this guy.” He rolled down the window and said, “Hey Finny!”

Haltingly, he turned and said, “Hi, Jack,” in a soulless voice while the woman kept walking.

“How the hell are you?” Jack asked, pretending he didn’t notice that his old friend looked bad.

“I’m dying,” he said and followed the woman.

Poor Finny. Jack called Charlie Samis later and found out that Finny’s liver was shot. Kidneys too. He was on borrowed time. Charlie said that on Finny’s last visit, the doctor had said, “I can’t believe you’re still alive.” What a thing to say to a person. Jack thought he’d like to find out who that doctor was and give him a good shot in the kisser. And so, later in the afternoon, he had walked down to Molloy’s Bar, because sitting at home Jack kept thinking of his old friend’s yellow face, and the words: “I’m dying.” And he had drunk too many beers, not to mention the shots of Jamie, but at least there was a ball game on the radio in the bar, and a few guys to talk to about whether Ted Kennedy was all done, and about whether they would like to go to the moon if they had the chance. Dick Guthrie said he’d go in a heartbeat, but everyone knows brave words in a barroom don’t amount to much.

Jack quickened his wavering pace because he had to piss. He walked up the front steps of 832 Westford Street but was having trouble getting the key into the door. He heard a screen rising in a window above him. The landlady, Mrs. Powers, leaned out.

“Mr. Sheils?”

“Yes, Mrs. Powers?”

“I thought that was you.”

“Yes, Mrs. Powers. My key…”

“Mr. Sheils, you don’t live here anymore.”

The thought clouds that had hovered over his brain began to thin, and he recalled that yes, he had moved out of this place. “Jesus Christ!” he said. “Excuse me, Mrs. Powers.”

“That’s all right, Mr. Sheils.”

He turned about and descended the steps but paused at the bottom and looked back up, where the old woman could still be seen in the window frame. He was all fuddled. He could recall the look of the new place, but for the moment couldn’t remember the best direction to get there. “Mrs. Powers?”

“Yes?”

He was feeling a bit light-headed. “Where…where is it I live now?”

“It’s 82 Harris Avenue, behind...”

“Oh, yes, of course. Thank you. Behind the church.”

“Would you like a cup of coffee, Mr. Sheils? I think you need a cup of coffee.”

“That’s very kind of you, Mrs. Powers. You know, I think I would like a cup of coffee, and if I could use your bathroom?”

“Of course.”

The old woman went into the kitchen to make coffee while Jack found the bathroom. He recalled the last time he had been in this apartment. He had heard a thud above him and came upstairs to discover that her husband Tom had fallen. He helped Mrs. Powers get him onto the couch, where Tom normally sat all day in his housecoat smoking Raleigh cigarettes and speaking in a jumbled way that only his wife could understand. He had returned to her from the Great War a shadow of the man she had married. Jack couldn’t recall if it had been gas or shell shock or what, but poor Tom was done. All done.

When Jack had taken a seat in the small living room, Mrs. Powers called from the kitchen, “How do you take it, Mr. Sheils?”

“No sugar, thank you. Dash of milk if you have it.” He looked around the room. The walls were papered with a botanical design, lush ferns and hanging leaves in muted colors. A bit Victorian, Jack thought, but reassuringly homey. A bowl of plastic apples sat atop a Magnavox television set. Neat writing desk with mail sorted into slots. Bookcase beside his chair. He leaned sideways to read the titles: Longfellow’s Poems. The Conquest of Mexico. Little Women. Emerson’s Essays. Forty Easy Meals You’ll Be Proud to Serve. There was a photo of her late husband in his military uniform on a side table, and above the couch where her husband used to sit, a painting of a ship that appeared to be struggling in a storm. Oval braided rug. All order and peace here, and it made Jack feel calm. The smell of old Tom’s cigarettes still lingered under the smell of furniture polish, giving his ghostly presence substance.

When she came in with the coffee on a tray, he rose instinctively, but she told him to sit down, she had everything in hand. “Now drink that,” she said. “And shall I make you a ham and cheese sandwich?”

“Oh, no thank you, Mrs. Powers. This is an awful lot of trouble for you.”

“Well, as my old mother used to say, it’s not very Irish to offer a guest something to drink and nothing to eat.” Before she went back to the kitchen, though, she went to a hall closet and came back with a fan. She moved her husband’s picture and put the fan on the table directed at him. “Very warm tonight,” she said and went off to the kitchen while he sat placidly sipping his coffee and listening to the sounds of a dish retrieved from a cupboard, the jangle of silverware in a drawer, a jar of mayonnaise set down and meat unwrapped. The sounds and his position brought him back to the day when he first returned from the war and his mother hugged him and cried, pushed him into his father’s stuffed chair and ran off to the kitchen to get him food.

“You’re too kind, Mrs. Powers,” he said when she set the sandwich on the hassock in front of him. Only then did he realize that he was hungry and began to eat.

“Well, I do miss you, Mr. Sheils. You were a fine tenant. Up every morning and out to work. Lights out at ten o’clock. Kept the front walk shoveled in winter. Helped me with Tom that time.” She shook her gray head. “And thank you for coming to his funeral.”

“Not at all. You were very good to him. And he sacrificed a lot for his country.”

“Yes, he did. We all did. I often recall the words of Milton: They also serve who only stand and wait.”

He nodded and swallowed. “Yes.”

She sat up then and smiled indulgently, “Now I never knew you to be a big drinker, Mr. Sheils, except at Christmas, maybe. I hope nothing is troubling you.”

“You needn’t worry. It’s just…did you ever feel a sense of foreboding?”

“A premonition?”

“Not a premonition of anything in particular. Not like, you know, I’m afraid to get on this airplane. It’s just…I don’t know. It’s the country. It’s a bad time. Ted Kennedy drove off a bridge with that young girl. She went under, and he didn’t call the police. He just left. Why would he do that? They say sometimes there’s an air pocket in the cab of the car. What if she was alive for some time? Why didn’t he wake up everyone and get help? Get the divers down there.”

Mrs. Powers sighed. “He says he was confused.”

“His brother wasn’t confused after an enemy destroyer cut his PT boat in half in the middle of the night, and the oil burned in the sea all around them. He took command and saved lives. A leader has to keep his head and do what he can do.” He shook his head. “It’s a bad time. About two, three weeks ago, Life magazine published photographs of 242 young kids killed in Vietnam in one week. One week. And nobody is sure what we’re supposed to accomplish over there. And then today, I saw an old friend and it seems his liver is gone, and he told me he was dying. That’s all he said. I said, ‘How are you?’ And he said, ‘I’m dying.’ And he walked away. What do you say to that?”

“Oh dear,” she said. “My, my.”

“And I find myself wondering, or worrying really, about these guys up in that little capsule hurtling through space. How far is the moon, Mrs. Powers, do you know?”

“Yes, as a matter of fact, I looked it up in my encyclopedia today. It’s 240,000 miles away.”

“And sometimes it looks so close. But think of that. It’s what…three thousand miles from Lowell to the Pacific Ocean? Think of all the cities and plains and rivers and mountain ranges and trackless rolling forests and vast deserts between here and there. That’s just three thousand miles. They’re going two hundred and forty thousand miles away from every other human. No one has ever been that alone. America needs heroes badly right now, Mrs. Powers. And I’m so proud of them, you know, but I find myself very tense lately. Worrying about them.”

“Yes. I can understand that Mr. Sheils.”

“That’s why I overdid it a bit tonight. All of that.”

“Yes.”

He took another bite of his sandwich and sipped his coffee. The old woman watched him. The fan blew his graying hair. Her husband had never been fit to have children with her, and how could she have raised a child with him anyway? She thought that if she had had a son, he might be around this man’s age.

“It’s none of my business, Mr. Sheils, but did you never think to get married? You would have made some girl a fine husband.”

“I became a cynic, Mrs. Powers. Would my parents have brought me into this world if they could have known that in my prime of youth I’d be sent off to war? I don’t think so. Not if they knew what that meant.” He paused and looked down at the braided rug. His brow furrowed as if he were trying to solve a problem. “In May of ‘45, just a few days after the surrender, I accompanied medics of the 5th to Czechoslovakia. Helmbrecht. It had been a concentration camp for women. I won’t describe it, Mrs. Powers. I can’t describe it. You lose, or I lost, the will to bring children into a world with so much evil in it. And suppose I had come home and married a nice young woman and had a son. It’s the same thing all over again. Two hundred and forty-two boys in a week, Mrs. Powers. Maybe my son would be one of them. Or like this poor Callery boy they renamed Highland Park for just a few years ago. Or, forgive me, your husband who suffered so much from the First World War. It goes on and on. People never learn.”

The old woman looked at her hands as if she could find some answer there and then clasped them together, twisting the gold band of an old promise on her finger. “I can certainly understand your feelings, Mr. Sheils.”

He finished his sandwich and rose. “I feel so much better. I guess I hadn’t really eaten today. Thank you, Mrs. Powers. Sorry to trouble you like this. What a dope, standing at the door with the wrong key.”

“We are creatures of habit. It’s no trouble at all. Do take care of yourself, Mr. Sheils.”

“I will. By the way, I was happy living here. It’s just, there’s no yard here, you see, and I wanted to have a bird feeder, and you know, be able to watch the birds. I want to sit in the yard and watch the sparrows, the blue jays, the cardinals. It relaxes me. Read the paper out there. I like being outside.”

“You don’t need to explain anything to me. They say a change is as good as a rest.”

“I just wanted you to know.”

He took her hand in his and held it warmly, thanking her once again. She reminded him that they were going to show the moon landing on the television the next evening—she didn’t know what time. “I’ll be praying along with you, Mr. Sheils,” she said. “They say they plan to land on a part of the moon called the Sea of Tranquility.”

“Beautiful name,” Jack said.

“Lovely name, isn’t it? Poetic. Like ‘the infinite meadows of heaven.’ That’s Longfellow.”

On the way home, Jack stopped at Highland Park—Callery Park now. He said a brief prayer for Billy Callery at the stone memorial. PFC Callery had joined that endless column of ghostly infantry. Jack didn’t know if it made any sense, or whether it was a good war, or if there was such a thing. But he had nothing but respect for those dead; all the young soldiers who once stood shoulder to shoulder under a rain of fire and wore on their shoulders the insignias of their units, the Big Red One, the Lucky 13th, the Pathfinders.

So many had never known old age, but by God, they had known brotherhood.

Jack wandered farther into the park and sat on one of the old swings that had rocked him through the air as a boy. The clouds had moved on. Gripping the cool chains in his hands, he leaned back and saw above the belfry of St. Margaret’s Church, a half-moon like a glowing cup in the sky. Tears gathered in his eyes, as he whispered to the infinite meadows of heaven. “Come on, Apollo! Fly right! Do it, men! Christ Almighty, we need some good news down here.”

'Legends of Little Canada' in The Boston Globe

Little Canada demolition, 1964 (photo courtesy of UMass Lowell Libraries)

Jack Dacey Reviews Steve O'Connor's New Stories

Lowell-based playwright and author Jack Dacey (J F Dacey) sent this soaring review of Stephen O’Connor’s new book of short stories. While not originally written for print, Loom Press asked permission to post the robust review on this blog, and Jack agreed. Below, we share it with everyone:

I finished Northwest of Boston (sometime in late April.) Steve, I don't know where to begin, or how to begin. I don't want to embarrass you by gushing all over the place. And, as the house philosopher at McCullough's Pub, I feel I have a certain standard to uphold!

I would like to say it was magnificent -- but that's a word people usually apply to great cathedrals, or symphonies, or palaces and gardens. Part of the beauty here -- and part of the magnificence -- lies in its lack of spectacular trappings or proportions. It's eloquence lay in its honest, direct prose that, to me, was totally devoid of even the slightest pretense or even hint of grandiosity. The beauty was what, to me, the reader, was the absolute truth of what I found on the printed page. Additionally, to me as a life-long Lowell guy, was a sort of misty-eyed familiarity, a grinning connection, something that made me nod my head slightly, constantly, as I read story after story, enveloped in what felt like a blanket I had owned all my life. This was Lowell! That picture we always have, of the cloudy skies, the long shadows, the brick walls, cobblestone streets, and always the lofty smokestacks -- all that was there. But at the same time, all that was the setting! Lowell lived and breathed and moved through the people who lived on your pages! I could see the ragged cuffs, the worn shoes, the flannel shirts with threadbare collars, the callused hands, the whiskered faces, and the watery eyes. Person after person, I either felt like I knew them on the first page, or if not, I knew them by the end of the story.

So many of them, I felt that they were people I had hauled in my cab. That's what they felt like. And in those brief moments when you share their company, a little bit of them rubs off on you. There were moments when I felt that this was the book I had been trying to write with Take the Long Way Ho me, but fell short. Or, it felt like Take the Long Way Home without the cab (if such a thing were possible.)

At the risk of repeating myself, the eloquence was in its lack of overt eloquence. It achieved a straightforward, plain-spoken directness that never failed to hit the mark, and, to quote myself, it always went down like honey.

I really appreciated the variety of the stories and the characters that inhabited them. Of all the stories, I would still rank Down to the Crossroads as my favorite -- why not? I had a featured cameo! Others that stand out would include: You Have Reached Your Destination; El Greco; Eschatology (years ago, for a brief time, I had a girlfriend, Celine Lajeunesse); A View From the Summit; and St. Lucy's Day (which I would still like to try to adapt to a short play.) But they are all masterpieces in their own way, each in its own way. The book is a tremendous achievement, Steve. I hope you are proud of them, because you should be. I will read these stories again and again. Many times I would think to myself: Damn! Why can't I write like that?

BTW, I seem to recall reading a couple of the stories previously, as you had posted them online. “Thy Sister's Keeper” was one, and I believe “September” was the other. This would have been a few years ago.

Well, anyway, Steve -- I think you get the picture here. Congratulations on Northwest of Boston. It is absolute ART with no soundtrack and no CGI special effects! Well done in every respect, my friend!

J F Dacey’s book Take the Long Way Home chronicles his overnight cab-driving experiences in Lowell in 1979. The book is available on amazon.com

What Shapes a Life? Ann Chandonnet Reviewed by Susan April

What Shapes a Life?

In Ann Fox Chandonnet’s new book: The Shape of Wind on Water, New and Selected Poems (Loom Press, 2023), her shaping began on an 180=acre apple and dairy farm on Marsh Hill in Dracut, Mass., in the arms of her Great Grandmother. In Chandonnet’s poem, “Voice Lessons,” we meet Great-Gram, Addie Richardson Fox, a woman born during the Civil War and who “left the farm,” as Chandonnet puts it, at the close of World War II.

All I can see now is her photograph;

she stands among bushes.

dark they are

like her severe dress,

severe like her face,

like the musty covers of her methods books

in the attic’s peeling trunks.

Great-Gram—severe as she may have been—nevertheless was the source of Chandonnet’s love of words. Like a spring, Great-Gram chants, croons, and pats little Ann’s hands as she carries the newborn about the house and the land. This collection of poems, old and new, is like a journey fulfilled that began on Dracut soil.

And what a journey. You’d be hard pressed to find another 1940’s-era Lowell-born, Dracut-raised woman who had, as her first job, teaching school on Kodiak Island in Alaska. In this collection, poems about those 34 years in the Far North mix with ones about life in a log cabin in North Carolina, as well as time spent in the California Sierras. In every poem, though, I hear those Dracut farm echoes, like Great-Gram’s voice from the hayfield.

As in the poem, “Learning Eskimo Dancing/Lighting Up the World:” The drumbeat is a brook rippling over shale / soothing as Gregorian. Or in “Sitka:” A root puts its arm around the shoulder of a stump / the upward spiral of Swainson’s thrush / pierces the underbrush with a spear of song. There’s Great-Gram singing. Because what shapes you, nurtures you, all of your days.

I am drawn to Chandonnet’s poems about the land. She writes in a disarming way of discovering an ermine behind the living room drapes, or a snowshoe hare rattling the cooking pots outside her tent on Tuckerman’s Ravine—a domestic intimacy that plays off the cultural tropes of ruggedness one expects from the wilds of Alaska or a cirque on Mount Washington.

My favorite in the collection is “Sides-to-the-Middle”—and yes, it’s about Addie Louise, good old Great-Gram, and a bedsheet she had repaired over and over because: Yankee thrift, but also: to preserve beauty. Something that Ann Fox Chandonnet does masterfully herself, in her life’s journey of words.

This sheet has travelled from Massachusetts

to California to Alaska to North Carolina—

has seen more of the world than great-grandmother did.

No matter.

Now frost threatens the new weeping cherry tree,

and knowing Addies love of cherries,

I pull out the sheet.

I staple it over the mouse-ears of green.

It flaps in the wind: a vanilla lollipop.

A week later, the tree blooms.

_______

Susan April, born in Lowell, Mass., and raised nearby in Dracut, has published poems and essays in literary magazines, anthologies, and blogs, including The Lowell Review and When Home is Not Safe. A longtime environmental scientist, she lives in Maryland.

Stephen O'Connor gets a shout-out from UMass Boston Alumni Magazine

Boston Globe Praises 'Barnflower' by Carla Panciera

In New England Literary News (5-14-23), Nina MacLaughlin of the Boston Globe praises Carla Panciera’s memoir Barnflower:

“Rowley writer publishes new memoir of a childhood on a Rhode Island farm

“Rowley-based author, poet, and longtime high school English teacher Carla Panciera grew up on a farm in Westerly, R.I., on “one-hundred acres in the middle of everything and yet completely invisible,” she writes in her new book “Barnflower: A Rhode Island Farm Memoir” (Loom). In 1952, Aldo Panciera bought what would turn out to be a very famous bull, making him a very famous farmer, changing the Holstein breed. Panciera’s respect for him, and the work, is evident on each page. The book illuminates the matter-of-factness of farm life: the smells, the sicknesses, the no-vacation-days hard work of it. And it’s a portrait of childhood, too, the popsicles and puppies and family games, and the other kind of hard work of trying to make sense of the adult world and finding a place in the world. More than anything, it’s a book about the love between father and daughter. Panciera shows that the power of what’s carried in the blood remains, even after the bull has died.”

Rhode Island Welcomes Carla Panciera Back with her 'Barnflower' Memoir

In The Westerly (R.I.) Sun newspaper, Nancy Burns-Fusaro writes about author Carla Panciera’s homecoming on May 4 with a book launch for her Barnflower memoir, which is receiving early praise from readers and critics. On theme with this story of growing up on a dairy cow farm, Carla will have a life-sized plastic cow outside the Savoy Bookshop and Cafe. Read the article/interview here.

Aldo Panciera with his prize cow.

Boston Globe praises "Beach Town: Stories" by David Daniel

Thanks to Nina MacLaughlin at the Boston Globe for kind words about the stories in Beach Town by David Daniel.

South Shore author focuses on the drama of small-town events in new short story collection

“Time, if fate allows, lets us become poets of the doomed action, the unrequited love, the hard struggle — and find humor in the human,” writes David Daniel in his new collection of short stories, “Beach Town,” out this month from the Amesbury-based Loom Press, and such is exactly what fate has allowed him. Daniel, who grew up on the South Shore, sets many of these stories in a fictional South Shore town called Weybridge, and focuses on small-town events — the opening of a new car wash, the arrival of a stranger in a leopard-print bikini, a skateboarder busting his two front teeth, borrowing an Oldsmobile, the “night air cool and secret in the low spots, salt-scented, and I’d let out the words.” The stories have the feel of reveries, remembrances, rich with nostalgia for the scent of the sea on a summer wind. “The only thing on fire these days, she thinks, is time, blazing away all around her.” The regular moments of the regular days turn out to be the most beautiful, meaningful, and humorous — haunting and human.

Praise for 'Barnflower" memoir by Carla Panciera

In ‘Motherhood, Literature, & Art,’ Jane Ward reviews the forthcoming memoir "Barnflower” by Carla Panciera.

“Barnflower is both a coming-of-age story and an unflinching examination of how a life can come to an end but also live on. At its simplest, it stands as a love letter to a father and a moment in time that will never be forgotten because now the stories have been told.”

Media coverage of 'Covid Conversations'--about the pandemic in Lawrence and Lowell, Mass.

Here’s the link to the extended report in the Eagle-Tribune of Greater Lawrence. Thanks to the newspaper for this attention.

Upcoming book events for "Barnflower" memoir by Carla Panciera

April 29, Saturday, 11:30 am: Newburyport Literary Festival, Newburyport, MA (more details to come)

May 4, Thursday, 6pm: Savoy Bookshop and Cafe, Westerly, RI

May 12, Friday, 6pm: Rowley Public Library, Rowley, MA

May 20, Saturday, 6-8pm: IAM Books, Boston, MA (with Mark Saba)

May 24, Wednesday, 6-8:30pm: Walnut Street Cafe, Lynn, MA

September 22-24, Common Ground Country Fair, Unity Maine.

October 14, Saturday, 2:30pm, Cranston Public Library, Cranston, RI